The ‘Core’ is a term that is thrown around whenever we mention back pain and/or exercise. But what do we really mean by the core? Commonly a good core has been associated with a strong back. In this article I hope to shed some light on this area, which as its name suggests, is a vital part of our body. I also hope to change the way you may think of your core, and challenge even some of the current teachings.

Let me start by discussing some of the common myths I hear about the Core.

1. Core muscles are found in the abdominal region.

Partly true.

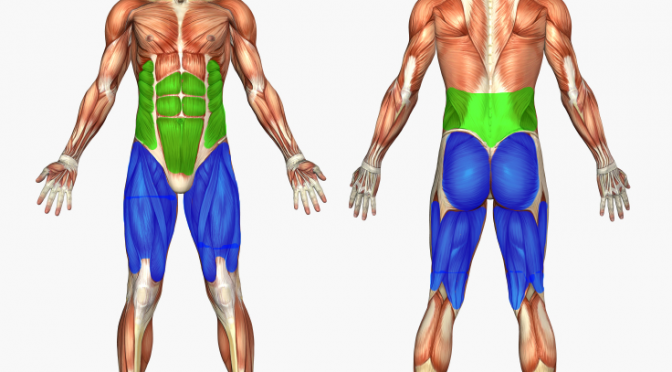

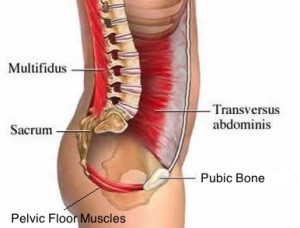

As the muscles of the pelvis and lower back region are some of the strongest and largest in the body, the muscles of the hips are now accepted as part of the core. Some of these include the glut muscles, pirformis, hamstrings and quadriceps (see blue muscles on image below). As all of these muscle attach to the pelvis and the pelvis is regarded as the foundation of the spine, the pelvic and hip region are now thought to be a vital part of having a good core.

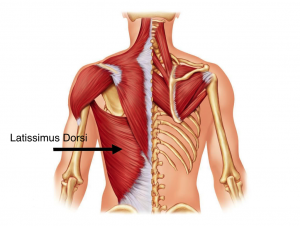

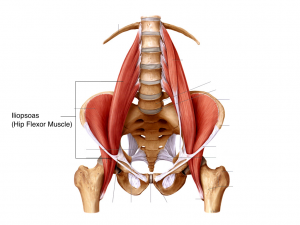

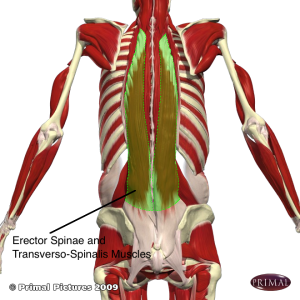

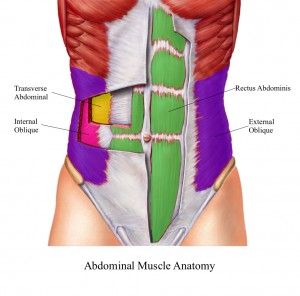

Traditionally the core has been referred to as a corset. Few of the muscles of the core act like a corset and squeeze the abdominal region inwards to form a tight cylinder. These muscles (the internal and external obliques and the transversus abdominus) form the walls of the corset and have been the target of many ‘core strengthening’ exercises. However we must not forget that these muscles are only a few of the total number of muscles that are found in the region. Some of the other muscles extend downwards from the upper body (Latissimus Dorsi, Rectus Abdominus), some upwards from the hips (Iliopsoas), some flanking on either side (quadratus lumborum) and the remaining running down the spine (Erector Spinae and Transversus-Spinalis).

The pelvic floor muscles are also an area which is often overlooked as being part of our core. These muscles connect the pubic bone to our tail bone and so is involved in controlling the amount of tilting of the pelvis.

2. A ‘Six Pack’ equals a good core.

Not necessarily. We refer to the six pack as a ‘beach muscle’. Looks good, but doesn’t really do much more than that.

A good core involves having good control of the abdominal, pelvic and hip regions. Majority of the the muscles found in these regions are involved in strengthening and stabilizing the lower back, protecting it from injury.

The six pack muscle, rectus abdominus (see green muscles below), is a very thin muscle that runs from the bottom of the sternum to the pubic bone of the pelvis. It is also a superficial muscle, sitting in an outer layer of our anterior/front wall of our abdomen. It’s main function is to flex the spine i.e. a crunch or sit up or to control the speed of back extension. If you a lucky enough to have one (a six pack), it doesn’t mean you have a strong core and are immune to back injury. It generally means you have a low body fat percentage and/or you have worked hard on your abdominal region.

3. If i keep my core ‘strong and tense’ during exercise, my back is being protected.

Not true. Quite the contrary in some cases.

Previously physical therapists, personal trainers, pilates and yoga instructors have taught people to tense the core muscles by squeezing the belly button into the spine and maintaining a constant contraction. This contracts the muscles around the abdominal region, however, may be potentially damaging for someone who is undergoing complex movements such as running, jumping, swimming, cycling or even lifting an object from the ground.

Having a tense abdominal region would make sense if you were to maintain a static posture. However, our daily activities, especially exercise, require complex movements and so the core is regarded as being a dynamic entity. That is, one that is constantly changing from a state of contraction and relaxation.

Lets take a runner as an example. During the running action, the muscles of the core are contracting just as the foot hits the ground to prepare for the impact forces being transferred up from the ground on to the lower limb. After the foot hits the ground and passes under the body, the muscles of the core relax to allow pelvic rotation and the transition of the opposite leg to swing forward. The core muscles will contract again in preparation of the opposite foot hitting the ground and so the cycle continues. Essentially, if all the muscles were to remain tense and contracted throughout the entire cycle, it would make body a rigid and less mobile unit which may put higher loads of stressful forces on muscles, ligaments, tendons and joints, predisposing you to injury.

For more information on how to train your core, contact our team at North Sydney Sports and Chiropractic.